My Cart

Your Shopping Cart is currently empty. Use Quick Order or Search to quickly add items to your order!

Laura Fondario Grubbs

Laura Fondario Grubbs

Microbiology Research Specialist

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro

April 2016

Many emerging environmental and human health threats are found in both the developed and developing world. One such threat are cyanobacteria and their associated cyanotoxins.

Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are photosynthetic bacteria that rely on light for energy (4). Most cyanobacteria grow optimally at temperatures between 20°C and 30°C (6), but have been recorded in temperate lakes and reservoirs at cooler temperatures. Each cyanobacteria species may need a different complex set of conditions to survive and thrive. Many of the species can be found in water bodies throughout the United States.

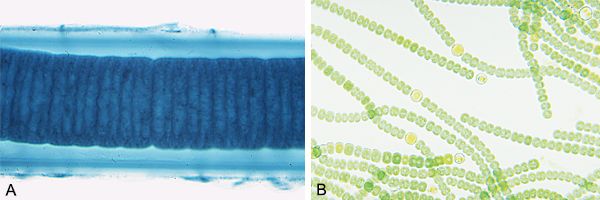

Photographs of Lyngbya spp. (A) and Anabaena spp. (B).

Lakes are particularly vulnerable to phosphorus nutrient influx, which is highly influenced by humans (7). With increased nutrients, cyanobacteria thrive and reproduce, causing water quality problems. Phosphorus loading is high in urban areas due to increased surface run off, wastewater treatment plant effluent, fertilizer application, and municipal and industrial pollution. In rural areas, septic tank drainage/leakage, soil erosion, and animal waste runoff contribute to phosphorus loading in lakes. At least 50% of the annual phosphorus loading in agricultural and urban watersheds is due to non-point sources (7).

When multiple factors are conducive to cyanobacteria growth, a rapid increase in abundance may result in a cyanobacterial bloom (4). A bloom may form dense filamentous growth called mats on surface water that can result in hypoxic zones (low oxygen levels) from decomposition and shading, which may kill fish and plant communities. Blooms can affect food web structure and/or destroy natural habitat (3, 7). A bloom can also be dispersed throughout a water column, and cyanobacterial abundance may not always be a deciding factor as to whether a particular cyanobacteria causes a problem. Some cyanobacteria are capable of creating cyanotoxins, which further amplifies the problems that blooms can create.

Cyanobacteria capable of producing toxins are referred to as toxigenic cyanobacteria. These toxins can affect the liver (hepatotoxins), the brain and neuromuscular system (neurotoxins), or the skin and mucous membranes (dermatoxins). Hepatotoxins, such as microcystins and cylindrospermopsins, can cause elevated liver enzymes, hepatitis, vomiting, headache, kidney damage, malaise, and weakness, and loss of appetite (3). Microcystins are of particular concern because they can disrupt protein phosphatases, interfere with cell structure and mitosis, and cause liver failure and cellular death in animals. In humans, microcystins promote liver tumors (10).

Cylindrospermopsins have been known to cause respiratory arrest in mice. Neurotoxic anatoxins can cause involuntary muscle movement, convulsions, and death. Cyanobacteria blooms linked to microcystins and anatoxins have caused mortality in bird populations, and cyanotoxin-contaminated submerged vegetation has been linked to avian vacuolar myelopathy (2, 3).

Blooms can present health risks to humans. Cases of gastrointestinal discomfort, respiratory distress, fatigue, swimmers itch, skin rashes, joint pain, and nausea have been linked to cyanobacteria (5, 3). Patients in a Brazilian hemodialysis unit experienced visual impairment, vomiting, intestinal bleeding, bloating, blindness, jaundice, and acute liver failure that were linked to cyanobacteria (9). Investigators found unfiltered reservoir water containing cyanotoxins in the dialysis tubing of these patients from a nearby lake. Of the 126 patients who reported illness, 60 died. Microcystins were found in the blood and livers of the patients (9, 2).

Cyanobacteria are an emerging environmental and health concern. Global warming and climate change are affecting the timing of lake stratification, precipitation, temperature, and drought patterns, providing conditions for cyanobacteria proliferation (8). Since many lakes are water supply reservoirs, increased populations of toxigenic cyanobacteria could pose health risks. Better analytical tools can help water quality managers and regulatory agencies assess and manage cyanobacteria and cyanotoxin abundance and develop better strategies to reduce environmental and health risk.