My Cart

Your Shopping Cart is currently empty. Use Quick Order or Search to quickly add items to your order!

Hay infusions are widely used as a source of microorganisms for studying decomposition, fermentation, and disease. As a hay infusion undergoes ecological succession, students will be able to observe different species and the fluctuation in their populations. A hay infusion is easily prepared from inexpensive materials—simply soak fresh or dried plant material in water.

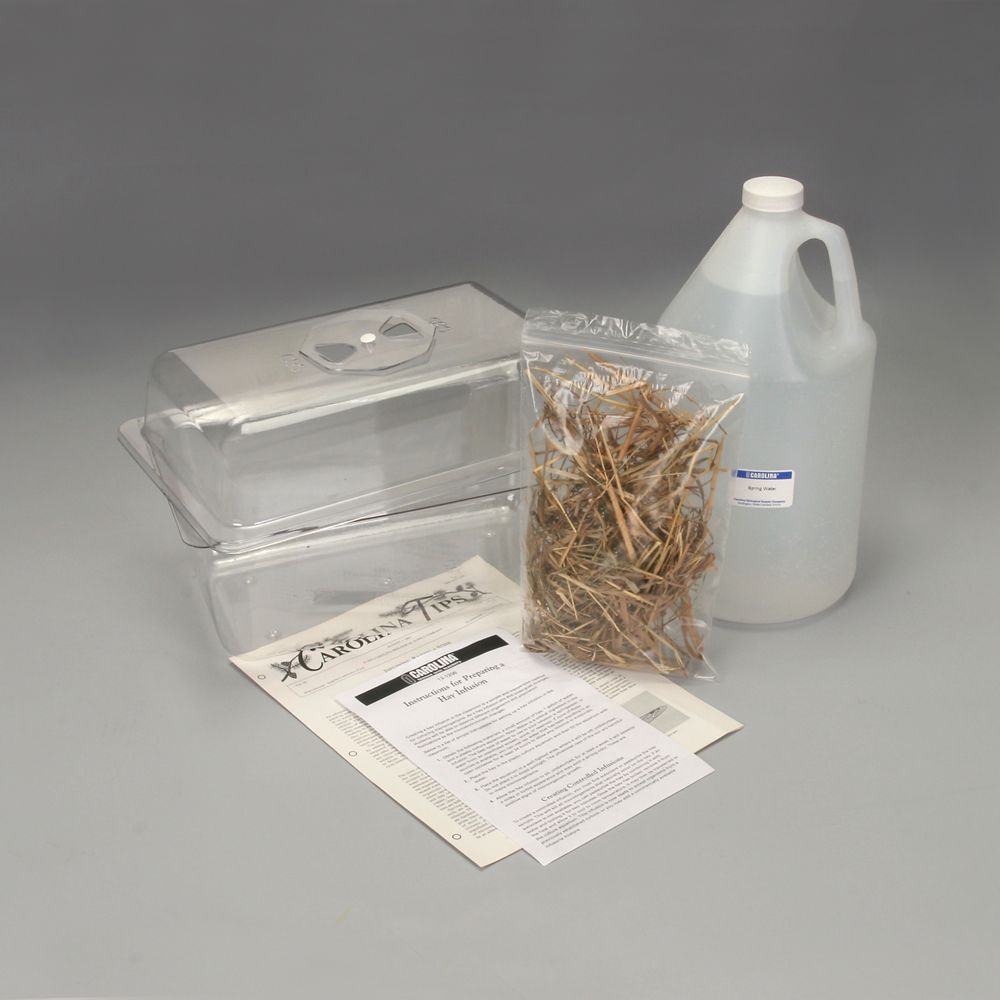

Hay Infusion Kit (131206), which includes:

Timothy Hay (132385)

springwater*

small aquarium with lid

*If springwater is not available, use water from an unpolluted stream, pond, or reservoir. If none of these is available, use tap water that has been treated with a water conditioner.

Protoslo® Quieting Solution (885141)

Ensure that students understand and adhere to safe laboratory practices when performing any activity in the classroom or lab. Demonstrate the protocol for correctly using instruments and materials necessary to complete the investigations, and emphasize the importance of proper usage. Use personal protective equipment such as safety glasses or goggles, gloves, and aprons when appropriate. Model proper laboratory safety practices for your students and require them to adhere to all laboratory safety rules.

The organisms that will live in the hay infusion are not parasitic or pathogenic. Even so, be sure to follow your district’s guidelines so you are prepared if a student ingests a culture. After completion of the activities, dispose of any remaining cultures according to district guidelines and procedures.

Students can work individually or in pairs.

Preparation of Hay Infusion

Information for the Instructor

During the first week, a surface film may form and the water may look milky and turbid. These are signs that the bacterial population is increasing. After approximately a week, bacteria and protozoa should be visible under a light microscope. Most organisms can be observed at a magnification of 200×.

The sugars in the hay provide the base for a food web. Bacteria feed on the sugars, and protozoans feed on the bacteria and on one another. If the bacterial community grows quickly, so will the protozoan community. The protozoa require oxygen; we recommend using a pipet once a day to bubble some air into the infusion.

A maturing infusion provides a food web based on the plant products originally produced from captured sunlight and stored by the decaying plant material. During subsequent weeks, students will be able to observe flagellates, ciliates, diatoms, and amoebas. These organisms will be present in different areas of the infusion. Certain organisms seem to flourish at different depths because of their adaptation to the subtle differences in factors such as temperature and dissolved oxygen concentration. Discourage students from unnecessary stirring. Any mixing may upset the balance between the microorganisms and the factors that enable them to flourish at a particular level.

Continue to feed the hay infusion by adding more springwater and hay weekly. Have students record any changes in the microbial community.

Two Types of Hay Infusions

There are 2 basic types of infusion used in classrooms: nonsterile and sterile. Students can use both in conjunction to study local microbial life. Infusions prepared from field-collected water or field-collected material usually require no additional inoculation from established cultures or other sources. Once the infusion is established, organisms can be selected and isolated using a microscope. They can then be transferred to a sterilized infusion to create a monoculture of the organism. Many of the current cultures at Carolina Biological Supply Company were established using this method; e.g., our culture of Amoeba proteus derives from specimens collected in the 1930s.

To prepare a sterilized infusion, sterilize the hay and water to kill cysts, spores, and other organisms that naturally occur in the plant material and water. A sterile infusion is usually set up for subculturing organisms from an established culture. By periodically setting up subcultures, it is possible to maintain protozoa for many years. For more information on culturing techniques, see our Carolina™ Protozoa and Invertebrates Manual available at www.carolina.com.