My Cart

Your Shopping Cart is currently empty. Use Quick Order or Search to quickly add items to your order!

Victoria Lin

Victoria Lin

Amplyus, LLC

November 2016

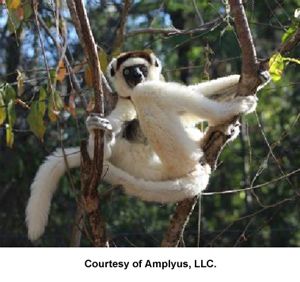

How do field researchers transport the samples they collect in remote locations to a location where they can be studied? Researchers like Elain Guevara have wrestled with this issue for years. As a PhD candidate in biological anthropology at Yale, Guevara made regular trips to the dry, spiny forests of Madagascar to visit a wild lemur population. Multiple groups, including her own, were focusing on this lemur population as the subject of their long-term research. In particular, Guevara focused on the population’s genetic history and diversity, which she studied by capturing the animals and taking cheek swabs once in their lifetimes—a frequency (or, rather, infrequency) that made each sample precious.

But the colony of sifaka lemurs Guevara studied at Beza Mahafaly Reserve in southwest Madagascar was endangered, and the logistical gymnastics required to transport biological matter belonging to such a species were complex. By the time researchers were able to remove the samples from the distant island nation and send them to a lab where Guevara would be able to extract and amplify the DNA, the swabs had already spent long periods stored in less-than-optimal conditions, jeopardizing their quality and the analysis that could be performed on them.

Considering an alternative

Considering an alternativeGuevara considered an unusual alternative. If the difficulty lies in bringing samples to the lab, she wondered, why not bring the lab to the samples? She had heard from a colleague about a portable thermal cycler produced by the biotech startup Amplyus. It seemed promising as a solution to her problem—a machine that she could carry into the field to amplify DNA on the spot. Powering the miniPCR® through a lithium ion battery that she charged from a small solar panel, Guevara was able to begin performing whole genome amplification (WGA) assays straight from the remote Madagascar field site.

One question remained: Would the WGAs work? That is, would the miniPCR® be able to stand up to the task at hand as well as to the bench-top machines upon which the team had previously relied? The answer is yes. “The miniPCR® seems just as effective as a traditional thermocycler, but of course is far more transportable, durable, and energy-efficient,” says Guevara. She found a way to overcome the challenge of transporting her samples—and the resulting enhancements in the condition of the DNA and the extent of analysis that can be conducted on it speak for themselves.

Today, having returned from Madagascar after a first round of gene analysis, Guevara is excited about the horizons her research has opened up, and she hopes to continue to use the miniPCR® to facilitate her findings. “The use of the miniPCR® represented a major improvement for us because we were able to obtain and amplify DNA right there in the field,” she says. “Going forward, I am hoping the miniPCR® will also allow us to do even more of the genetic analyses in Madagascar. I think miniPCR® is ideal for the field.” Elaine’s microsatellite genotyping of these lemurs will help determine relatedness for the population. It can also answer questions about mating strategies, fitness, and dispersal, as well as help reconstruct the demographic history of the population and assess their genetic diversity.